As we celebrate Haruki’s Murakami ‘Princesa de Asturias’ literature award, it brought back the memory of the Murakami’s book ‘What I talk about when I talk about running’, a precious reading for those that enjoy reading, and also running.

As a runner, I will always remember the passage when Murakami is finally running a marathon, and his description of the mental fight at the very end of the race to avoid walking and keep running to the finish line. We (marathon runners) know how hard these final meters are (and sometime kilometers, depending on your resilience).

I also admire how Murakami describes running activity as a way of inspiration and meditation for his ongoing writings. In this regard, I recognize myself when training around the city, and observing the surrounding architecture as a way of contemplation, admiration, and sometimes inspiration for my own ongoing architectural projects.

Can’t think of a better place to do this than New York City. During my several years of training around the city (9,217 Km around the 5 boroughs, and counting) I ended up planning my routes around the architectural marvels that the city offers. Contemplating the landscape, some of its staggering civil engineering structures, and mostly the buildings, provided an incredible source of inspiration, beside making those miles to seem shorter.

Here I propose three of my favorite routes around Manhattan in connection to the architectural landmarks to be found. For the avid runners these runs can be performed on a single run, but otherwise can be split into segments and do the return trip by using the subway (carrying a MetroCard is always a helpful tip, in case weather deteriorates or your legs are giving up).

Run #1 - Roosvelt Island or ‘the fathers of modern architecture.’

Run #1 – the fathers of modern architecture

This run map also includes the Central Park (see run #3 below), but for now I’ll focus in the passage from Manhattan to Roosevelt Island. In order to cross the East River from Manhattan, go to the north side of the Queensborough bridge at 56th St between 1st and 2nd avenue. There’s a cycling and walking path that crosses the bridge. This is a great run for training up and down hills, as the bridge provides one of the longest gradient elevations to find running around Manhattan (there’s an almost 5% gradient slope, a 20m height climb).

Gustavino’s vault under Queensboro Bridge

Right before getting into the path, there’s one of the Gustavino’s tile vault works (now a Trader Joe’s supermarket under the bridge). These are the same popular tile vaults you might find in Grand Central. Take a quick peek inside the market. Rafael Gustavino was a Spanish architect that moved to NYC in 1881. His patented version of the ‘catalan vault’ (a historical brick arch with its origin in the roman times) made him famous. His design provided a sleek way to resolve big spans between columns.

Queensborough bridge pedestrian and biking path

The Queensboro bridge was erected between 1901 and 1909 with a collaboration of the same architects that designed Williamsburg bridge, Leffert L. Buck and Henry Hornbostel, both led by Gustav Lindenthal. The bridge represents the constitution of Greater New York City and the amalgamation of the 5 boroughs. The original bridge considered the upper deck as pedestrian, with an adjacent construction to connect with Roosevelt Island, which was demolished in the 50s.

Once at the other side of the river, follow the riverside up north, to the Welfare Island bridge, which provides pedestrian crossing to Roosevelt Island.

Roosevelt Island provides a great continuous running loop around its borders, with magnificent views over Manhattan.

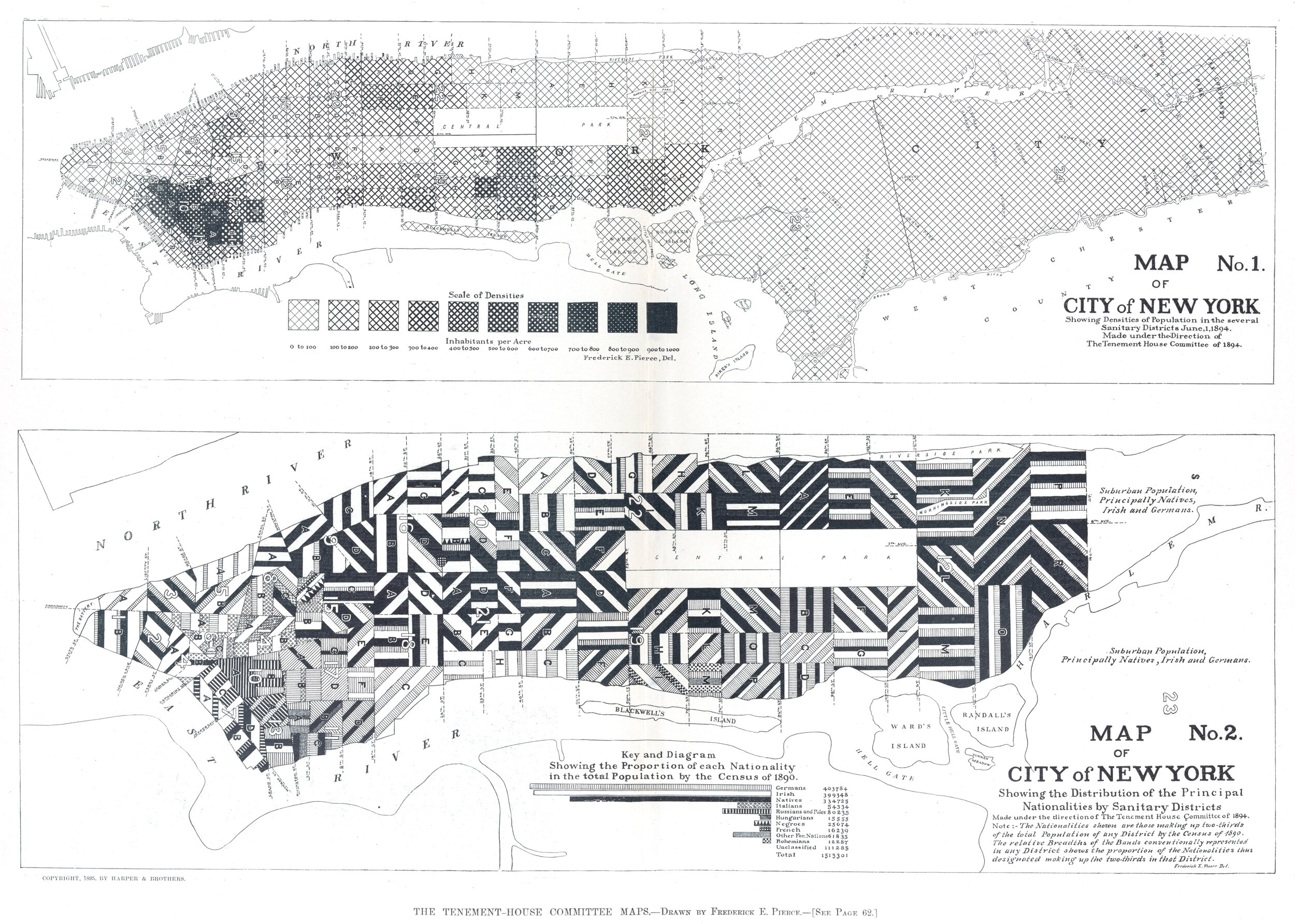

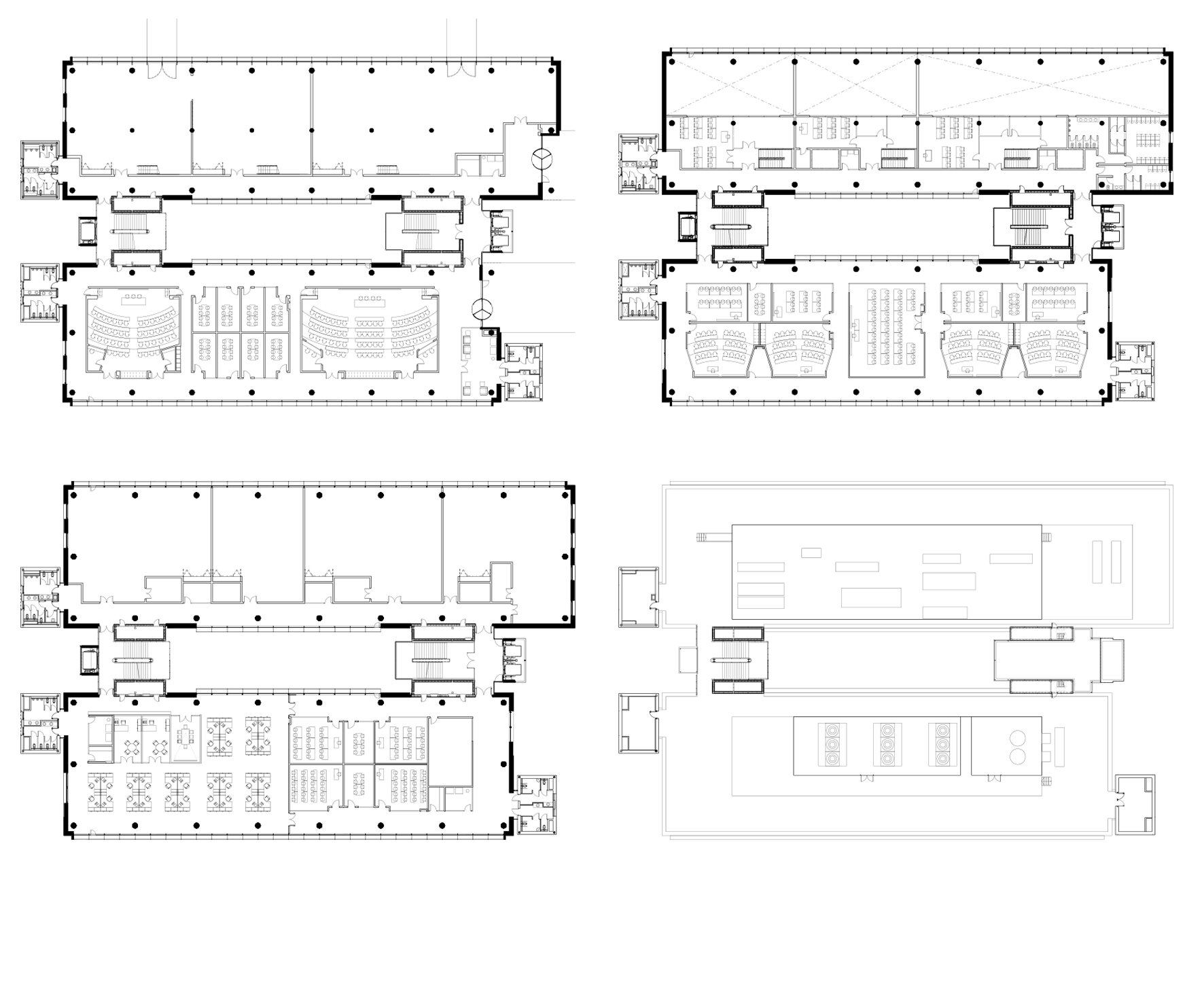

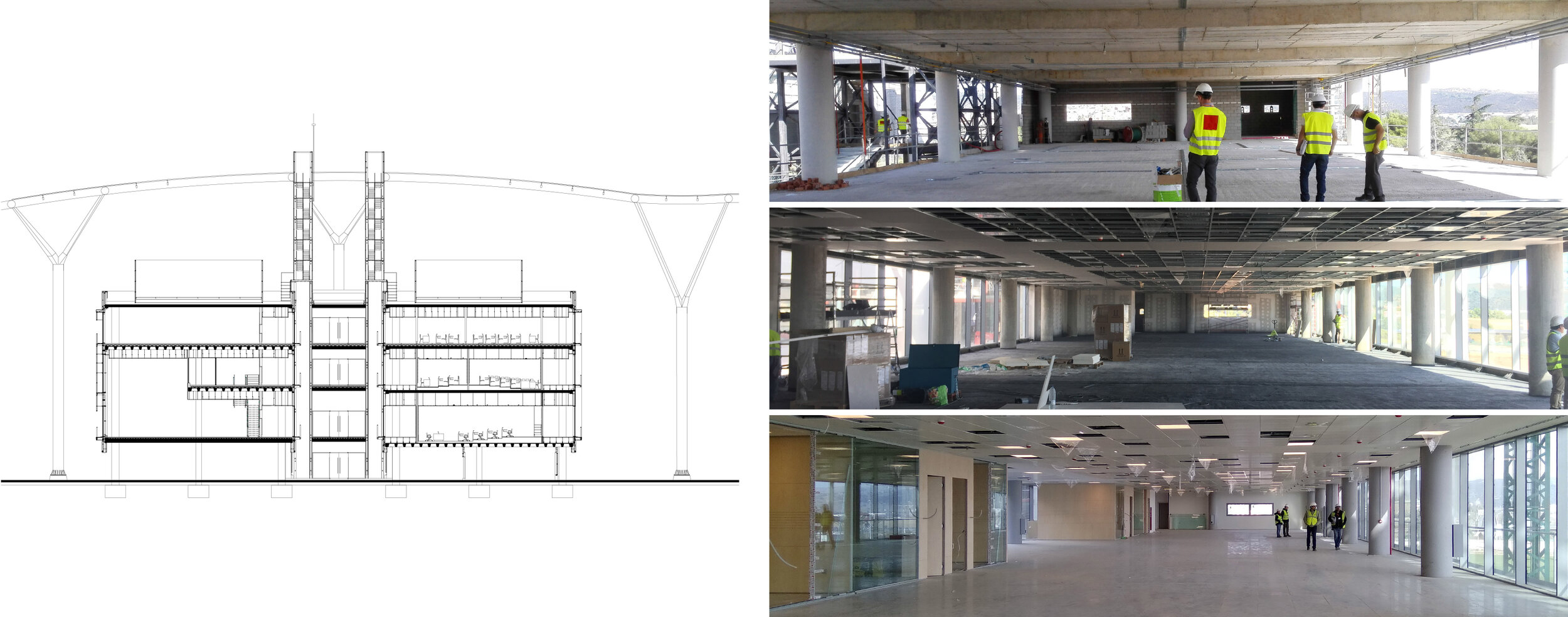

Sert’s Roosvelt Island housing project original as built plans.

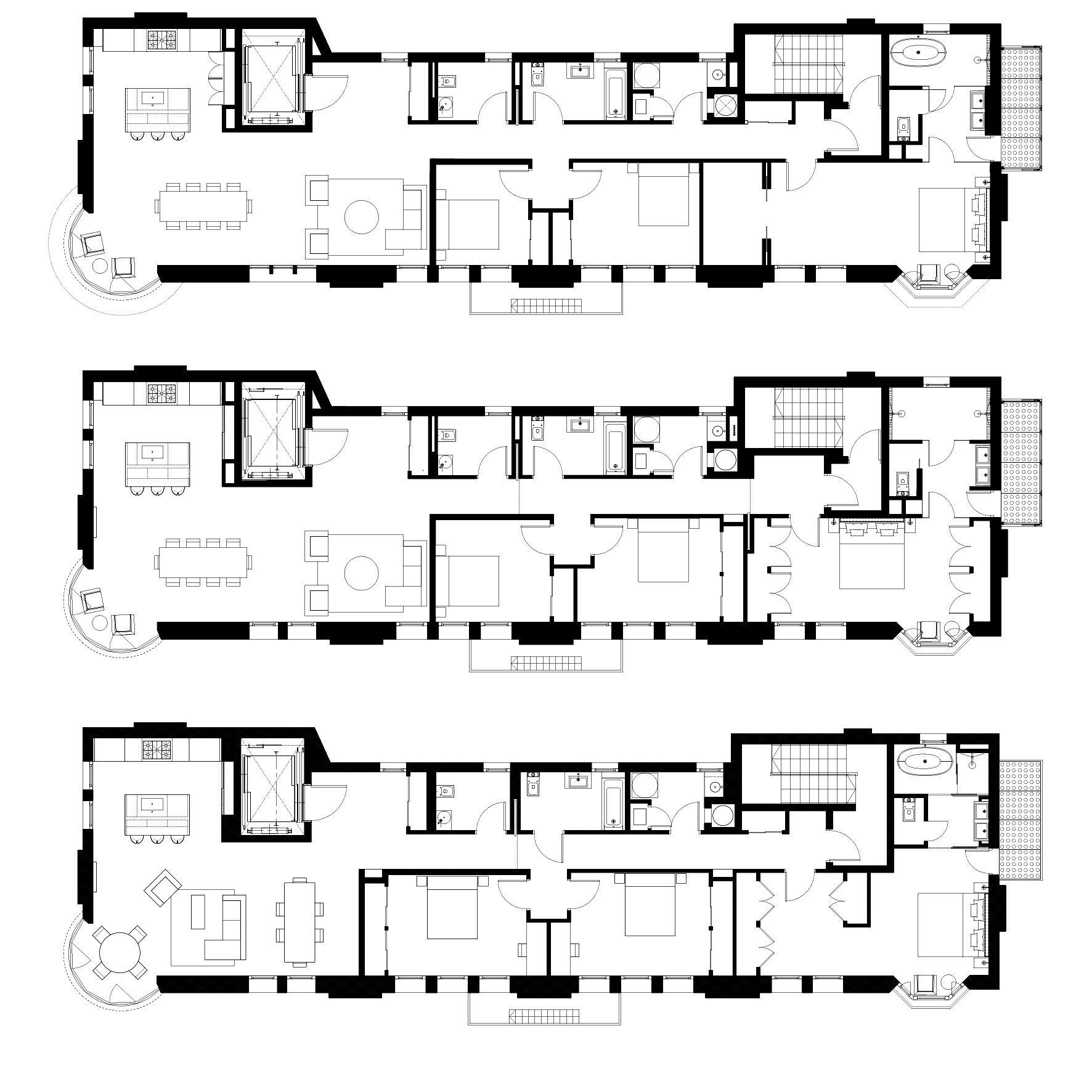

At the island, heading south from the bridge along the east side, is one of the largest projects ever designed by Spanish Architect Josep Lluis Sert. Sert emigrated to the United States due to the Spanish civil war. Close friend of Le Corbusier, he’s considered one of the fathers of modern architecture. The building clearly reflects that. Some of its sections are cantilevered over the streets, exposing the ‘pilotis’ system. The general massing escalates its high from the river (lower) to the town center (higher). Building’s stairwells are external, providing clear floorplates without internal vertical obstructions. The units inside maximize volume rather than square footage, so the apartments are ‘duplex’ or even ‘triplex’: because of this, the distribution corridors are only located every two or three floors, making possible locating them facing the exterior and getting lots of light. In 2019 as part of the 50th anniversary of the building I had the opportunity to visit, and despite the general deterioration of the building due to its age, the quality of the interior common spaces remains intact: hallways filled with light and views, and spacious entrance lobbies with double height ceilings.

Run #2 West Highway or the Pritzker Prize HIghway

Run #2 – the Pritzker Prize Highway

The West Side Highway provides what must be one of the longest uninterrupted runs in an urban environment. Starting at the South Ferry terminal it runs continuous without any street crossing way beyond George Washington Bridge. It crosses several Parks, and having clearly differentiated the path between cycles and runners, it is very safe to run on. The stretch to focus here is between 21st street and Clarkson Street where in the length of around 20 blocks it can be found the work of up to 7 Pritzker winners, making the stretch very unique and rich, architecturally speaking.

Norman Foster

Coming from the North, the first building to be found is a condominium building at the corner of 21th St by Norman Foster. I do remember following its construction, and it has a beautiful structural detail at the corners, where there is no column, allowing a continuous corner window without obstruction.

Jean Nouvel

Frank Gehry

Shigeru Ban

Renzo Piano

Further down at 19th St is another condominium building, this time by Jean Nouvel. It’s in the south facing corner, and the building features an exterior cladding with randomized glazing, in contrast with the north black brick wall, almost solid. Right in front of it is the IAC building by Frank Gehry, a building that resembles a set of sails. Each glass panel features a unique shape and size. The gradient pattern of the glazing provides a beautifully integrated sun control device into the building. Right next to it at 19th St there’s a low-rise condominium building by Shigeru Ban. Its minimal style makes it blend into the neighboring buildings, making it hard to spot. Named as ‘metal shutters’ the duplex apartments have an exterior motorized screen to provide intimacy inside. Further south between 12th St and Gansevoort St is the Whitney Museum by Renzo Piano, one of the latest additions to the area. Defined by Piano as a docked boat echoing the history of the area, one of the upper levels features an oversized picture frame window facing the river.

Richard Meier

Between Perry and Charles St is a set of 3 condominium buildings by Richard Meier. They feature a glass cladding with some of his signature white paneling. The flat curtain wall at two of the buildings provide a beautiful reflection merging the river at the opposite side with the blue skies. Between Leroy and Clarkson is another condominium building, this time by Herzog & de Meuron. It is an exposed concrete structure in a semi-rounded shape with windows from floor to ceiling. The thin concrete slabs matching the thickness of the columns, creates a harmonious structural grid, vertically and horizontally.

Run #3 Central Park

Central Park is the ‘patio’ of New York City. I have been there running, racing, walking, biking, skating, laying in the sun, watching theatre and movies, reading a book, listening a rock concert and a symphony orchestra. My very first run in New York was in Central Park. At that time, cars were still running inside in some of the sections. The original narrow running lane was shared with bikers, and you had to be constantly vigilant to avoid crashes. These days, cars are banned, so the entire old traffic lanes are now for runners and bikers; and without any street light crossing, is a 10Km non-stop continuous loop. One day I had the opportunity to have breakfast with Peter Ciaccia (NYC Marathon Race Director) and I told him the only thing Central Park needed to become the biggest Olympic Stadium and Track of the world, was to pour a tartan floor on the running lane: he loved the idea.

With Peter Ciaccia (center) the night before NYC Marathon

I do also like the ‘flexible’ runs the Park provides. You can opt for a very short loop, for example just around the Reservoir, on gravel; or extend the run a little bit using the traverse at 102nd St on tarmac; or go for full round and tackle Harlem Hill, the steepest climb in the park, and the rest of the hills along the West Side.

There’s a huge variety of architectural surroundings, from pre-war buildings on the west side, to the east side townhouses. But the portion that had a more profound change in the recent years is the south side skyline along 59th St, what is now referred as billionaire’s row. In the last 10 years there’s been an implosion of high-rise condominium towers.

Super tall residential buildings along Central Park South

Next to Columbus Circle is one of the latest additions, the Central Park Towers, a square glazed tower by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill architects, same designers behind world’s tallest building, Burj Khalifa. This building is currently considered the second tallest building in NYC, and the tallest residential building in the world. Between 7th avenue and 6th avenue is the One 57 tower by Christian Portzamparc, the building that re-started the race for residential supertall in the area in 2010.

Just behind it and topped using a copper faced dome is the City Spire building, a Helmut Jahn design which was the second tallest concrete building in US when completed in 1989 (after Sears Tower).

The Steinway Tower by SHoP Architects during construction.

Adjacent to One 57 is the Steinway Tower by Shop Architects. The building features a ‘sword’ shape as a result of the required setbacks for sky-exposure plane. Finished in terracotta, as an homage to a historical cladding material used in Manhattan, is the third tallest building in the city.

The MoMA Tower by Jean Nouvel during construction.

Behind it is the MoMA Tower by Jean Nouvel, another building topped with a sharp edge. Looking east is the 432 Park Avenue building by Rafael Viñoly, which features a square grid pattern façade, is the fifth tallest building in the city, and used to be the tallest residential building.

All pictures by Ignacio Alonso, taken during his runs.

Ignacio Alonso at the Reservoir